The newly confirmed ocean current is called the North Icelandic Jet.

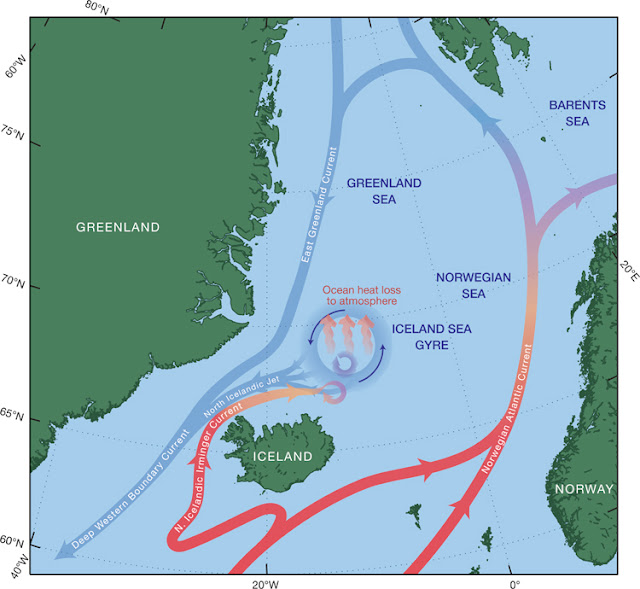

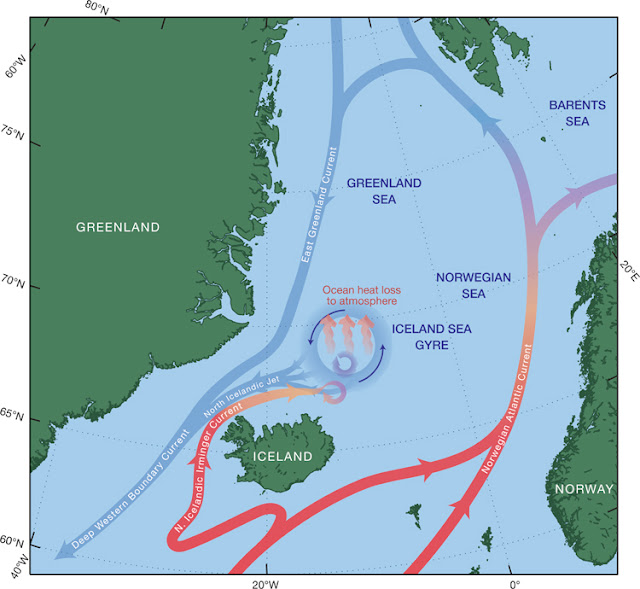

It feeds cold, dense water into the Deep Western Boundary Current, helping to drive the lower limb of the Ocean Conveyor, the global ocean circulation system that regulates Earth's climate. Warm water from the tropics eventually diverges south of Iceland, with one branch, the North Icelandic Irminger Current flowing west of the island. The current sheds eddies that dissipate into the Iceland Sea Gyre. The waters lose heat to the cold atmosphere in winter, become colder and denser, and sink. Cold, dense water leaks out of the gyre, coalescing into the North Icelandic Jet, which pools behind the Greenland-Scotland Ridge. The cold, dense water flows over the ridge and feeds the Deep Western Boundary Current. (Illustration by Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

A decade into the 21st century, scientists have confirmed the existence of a new and apparently crucial ocean current on the face of the Earth. International teams led by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) oceanographer Bob Pickart verified the previously unknown current near Iceland in 2008 and returned in 2011 to determine how it is formed.

The current, called the North Icelandic Jet, is not merely a curiosity. Though relatively narrow, it is an important cog in the global oceanic conveyor of currents that transports equatorial heat to the North Atlantic region and tempers its climate. Learning how the current operates offers insights into potential monkey wrenches that could disrupt ocean circulation and lead to further climate changes.

Initial evidence for the unknown current came in 1999 when Héðinn Valdimarsson and Steingrímur Jónsson from the Icelandic Marine Research Institute (MRI) used instruments measuring water velocity to detect a flow of dense water north of Iceland. But confirmation had to wait until 2008, when Pickart led a research cruise to the region aboard the WHOI research vessel Knorr. Taking detailed measurements of water properties and velocity, Pickart and colleagues from WHOI, MRI, and the University of Bergen in Norway confirmed the North Icelandic Jet, publishing their findings in Nature Geoscience in 2011.

But why was it there?

Pickart consulted WHOI colleague Michael Spall, who specializes in using numerical models to investigate ocean circulation. Incorporating known data and the laws of physics, Spall’s model painted a picture that could explain the North Icelandic Jet. In a sense, it was a tail-end tributary of a great river of water in the ocean, the Gulf Stream.

The Gulf Stream conveys huge amounts of warm, salty water from the tropics to the North Atlantic, where it meets cold air in winter, releases its heat to the atmosphere, and warms the region. As the water becomes colder, it becomes denser; it sinks toward the seafloor and flows back southward, driving the lower limb of a big loop, often called the global ocean conveyor. Waters in the conveyor then flow around the entire planet, eventually rise, and circle back into the Gulf Stream. Like a planetary plumbing system, the conveyor pumps water and heat around the globe and regulates Earth’s climate.

In the North Atlantic, the Gulf Stream diverges: The Norwegian Atlantic Current bends east to warm the United Kingdom and Scandinavia; a smaller current called the North Icelandic Irminger Current veers around the west of Iceland. The latter current was thought to dissipate north of Iceland with little or no further impact on ocean circulation. But Spall’s model indicated that the North Icelandic Irminger Current sheds eddies that cool and disperse within the swirling Iceland Sea Gyre north of the island.

Spall, Pickart, and Kjetil Våge, Pickart’s former graduate student at WHOI, now at the University of Bergen, proposed that the newly formed cold, dense water subsequently leaks out of the gyre, coalescing and sinking to form the deep North Icelandic Jet. This constitutes a local overturning loop in which warm surface water flowing north—the North Icelandic Irminger Current—is transformed into the deep, cold southward flow of the North Icelandic Jet.

To test this hypothesis, Pickart returned to the region aboard Knorr in 2011 with a team of researchers from WHOI, Iceland, Norway, and the Netherlands. Covering 3,812 nautical miles, they measured current velocities and water temperatures and salinities, precisely mapping the boundaries of North Icelandic Jet. They confirmed that it indeed forms north of Iceland and flows south to join the East Greenland Current.

Until now, the accepted theory was that only the East Greenland Current drove the lower limb of the conveyor in this region. Pickart and colleagues have now established that the North Icelandic Jet is a distinct current that supplies about half of the total water, as well as the densest water, that flows southward through the Denmark Strait, helping to drive the ocean conveyor.

As such, the North Icelandic Jet is part of a previously unknown regional loop of warm-to-cold water transformation in the larger loop that regulates Earth’s climate. As scientists strive to predict how rising global temperatures could disrupt the balance of the oceanic machinery and its impacts on climate, it’s crucial to know where all the integral parts are and how they work.

The Greenland-Scotland Ridge is a tall undersea ridge that rises within 500 meters of the sea surface and extends from East Greenland to Iceland and across to Scotland. The ridge acts like a dam separating deeper ocean basins on either side. In some areas dense, cold water eventually flows over the dam in an undersea waterfall. (Illustration by E. Paul Oberlander, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)